For Micki Ferrets and other Ethical Considerations

**NOTE: If you read this post in its entirety, please also be certain to read the comments. I do not purport to be an expert on plagiarism or on writing — I’m just another crazy who’s doing my best to tell a good story, and to write it in an ethical way. I might be corrected in the comments, someone might disagree with me and we’ll have to discuss a point, and there are many people smarter and more knowledgeable than I with something important to add that I might have left out. Also, I am coming at this from the perspective of a writer trying to avoid plagiarizing, not necessarily trying to define plagiarizing. If you’re looking for a definition, ask for one, and I’ll try to find some good links. UPDATED: Jane at Dear Author has just put one up.**

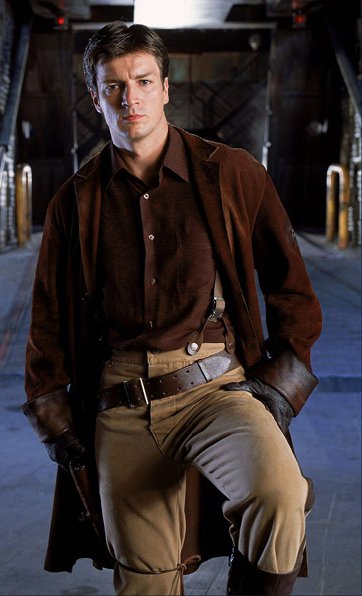

**NOTE #2: For those of you who intend to read my book, DEMON NIGHT, and who prefer to NOT know about the process behind the writing, some of my allusions and inspirations (including a picture of a celebrity that I used as a visual reference for the hero) you really, really shouldn’t click past the “more†link.**

In response to my Red Shoes post, Micki asked this question:

How can you *tell* when you’ve borrowed a heel, and how can you *tell* when you’ve borrowed the whole damn shoe? And is it *such* a problem if you borrow the shoe, as long as you change the characters and genre and make the shoe a side issue instead of a lynch pin?

And this was my quick answer, with a promise of a longer one to follow:

[…] my short answer is, even if you don’t know the exact rules, you know it in your gut. Retelling Sleeping Beauty is one thing; retelling Robin McKinley’s version is another. Knowing that something your heroine says is similar to something another heroine says is one thing; making your heroine say it BECAUSE the other heroine said it (and because you couldn’t think of anything of your own to put in her mouth) is another. Reading a description of St. Patrick’s Cathedral and letting your character describe it in her words, or describing it in your voice is one thing; plopping that description into your work with a few looks at the thesaurus and moving around a few phrases is another.

My long answer is still the same: You know it in your gut. I’m going to explain that a little bit more after the jump — for those familiar with my blog and and my e-mails and my novels, you probably know what’s coming. For those of you who aren’t, here’s a warning:

When I say long, I mean “I’ve pretty much written a book, and it circles and veers off on tangents and eventually gets to the point.†And to save everyone with little time a lot of time, the point is: You know it in your gut.

Or at least you should.

This is not going to be about WHAT NOT TO DO from the perspective of defining plagiarism. This jumps off from a basic understanding of plagiarism is taking something that isn’t yours, and calling it your own. This is about ethics, and making ethical decisions, and the process a writer (namely: me) goes through to make those decisions.

And I’ve mentioned before that I find these decisions very difficult to talk about without using concrete examples from your own work. Because it is easy to say, “don’t take what isn’t yours†— it is not so easy to know what that means and how to apply it in an ethical way. And it is easy to look up an academic website, and to see how plagiarism is defined and examples given of WHAT NOT TO DO, and at the heart, the rules for academic writing and fiction writing are really no different: don’t take what’s not yours and say it is.

I can’t say it enough. Don’t take what’s not yours and say that it is.

But, as Micki asks: how does a writer know?

I will be honest: a part of me is really confused by the question. My initial response is, How can a writer NOT know what’s theirs? Whether I’m having a great writing day, and it’s coming out smooth and quick, or a terrible one, where I’m fighting for every single stupid word and it’s horrible awful and I want to stab my eyes and go back to accounting for a living, I know what’s mine.

If it’s not mine, I’m going to make it obvious to a reader: I’m going to set it off with quotes or italics, I’m going to put something in the text as an indicator …

Oh, yeah. But sometimes … I don’t. But those times, you can be damn sure that I’m going to make it mine.

So, let’s get on to the examples in my writing where I’ve had questions about whether I should use something or not, and whether it really was mine, or stealing in some way (I’m going to use examples from my latest book, DEMON NIGHT, because it allows me to discuss in a concrete way (instead of a hypothetical) the process of making something yours, and deciding whether its use is ethical. Feel free to disagree with anything I’ve done.)

And this is also the first long tangent.

Oh — but first, here’s the sub-tangent. I believe that writing does not take place in a vacuum. (This sub-tangent comes complete with clichés!) Writing, to me, is part of a larger, cultural discussion that includes, comments on, responds to, and incorporates other texts. Unless a writer manages to become a writer without having read another book, listening to music, watching TV or movies, reading a newspaper, or talking to another human, their writing will be informed by a long and rich history. Even the words we use are informed by a long and rich history, and writing *works* because readers have that same history to draw from as the writer. The reader might not have exactly the same background and might draw from that history in different ways than the writer (no one reads the same book the same way) but — for the most part — there is a very, very large common ground of meaning between reader and writer within the text.

And so, within a work, a writer may unconsciously or unintentionally engage in part of that discussion and reference other texts, just because it’s floating around in the back of her mind. Other times, a writer deliberately includes references, either to create that ping! of recognition (that I think Nora Roberts first mentioned in one of the discussions at Dear Author, but I can’t find the link right now) within the reader, to set tone and mood, to inform character, or just as a nod to the other work and its place in that larger cultural discussion.

Okay, I know this all sounds very Wah! Wah! kind of like the adults in Peanuts, so this sub-tangent basically boils down to a cliché: we don’t write in a vacuum.

So, back to the main tangent: I was writing a romance book that needed a hero, and I knew that hero was going to be Ethan McCabe (aka Drifter). I’d introduced him in another book (DEMON MOON) — and his appearance was a brief one, less than two pages. Here’s the first physical description and some of his speech (the POV is from DEMON MOON’s hero, Colin.)

The wings vanished as the Guardian rose to his feet; with his brown hair, a long brown coat, and coarse brown trousers, Drifter was a mountain of a man. A bloody tall mountain of a man.

Drifter’s eyes narrowed as he looked at Colin leaning casually against the brick wall, and at a glance the Guardian took in the two figures at Colin’s feet. “I reckoned Agent Milton lied to me when she said that you were in danger.â€

Now, this is all mine. It’s not necessarily original — although I can’t think of an example off the top of my head, I know I’m not the first person to use a mountain to describe a man — but even though it’s not blazing any new trails through prose, it’s still mine.

But mostly, this example is just to illustrate how much we draw from small words and tiny cues, and how writers use them. The word “reckon†gives the reader a quick picture of Ethan that I know is drawing from a gazillion different sources. And some of the associations that readers have with the word “reckon†will be more negative than I intend, and I can’t control that … but that is where character development comes in, which the writer can control and use words and action to sharpen and deepen the reader’s view of a character. Of course Ethan isn’t just a big cowboy with a drawl, but IMO, half the fun of writing is taking something that simple and that quickly defined, and exploring it so that he can’t be summed up by a brief physical description and a word — and hopefully, the result is something that is something new within the cultural discussion. Not necessarily hugely new, like Gibson’s NEUROMANCER, but even a tiny bit new.

I mean, that’s what writing romance is about, right? Two people who meet, form a quick and superficial opinion based on very little information — and then that opinion changes through the course of the novel as they get to know each other better, and create something new out of it (like, um, love and a relationship — both of which aren’t new concepts either, but hopefully it creates a love and relationship that is uniquely theirs).

So I’ve got this hero — and this next part of the tangent is my personal writing process, which really doesn’t apply to anyone but me, but I think is necessary to illustrating my WHAT NOT TO DO decision-making — and I’ve brainstormed his character, and I know almost everything about his history, his personality, his physical appearance, and so on. (There are many things that I discover along the way and in the process of writing — things that pop up that I’ll play with — but for the most part, the core of his character is settled.)

But then I run into a problem, because I personally have difficulty writing a long text without visual cues. My hard drive is full of pictures and paintings, maps and weapons and landscapes and people and houses and more Hieronymus Bosch than is probably healthy. Much of that is for inspiration, setting a mood when I write. Some of it is for reference. And some of it is because I can’t keep a face in my head, and my brain has this blank spot when it comes to describing facial expressions on non-existent individuals. I can tell you exactly what my husband does when he’s upset, and it’s different than what my sister does. And although I can imagine and project an expression onto a fictional and non-existent face, the faces in my head kind of blur.

So when I write, I look for a single person to use as my reference for expressions, so that I can project what I imagine onto a real face. I know that sounds weird, and I’m not sure if that’s what other writers mean when they talk about using a muse. Because Ethan is already in my head, and I know what he looks like and know what he does — but at the same time, I want it to be…mentally tactile, I guess, so that my written descriptions are more real.

And then I make a collage with references to hero and heroine that I keep on my computer desktop. For Ethan, I looked around for a long time, but I kept coming back to Nathan Fillion, who played Mal Reynolds in Joss Whedon’s Firefly series and the movie Serenity.

And then I make a collage with references to hero and heroine that I keep on my computer desktop. For Ethan, I looked around for a long time, but I kept coming back to Nathan Fillion, who played Mal Reynolds in Joss Whedon’s Firefly series and the movie Serenity.

But I resisted it for a long time, because I knew that using that image meant that I would subconsciously engage with Firefly as a text on a deeper level that I wanted to in my book. Ethan is not Mal Reynolds, but they share a couple of character traits and superficially a few physical traits, and I was afraid of blurring the line between my character and Joss Whedon’s.

The truth is, though, I was probably drawn to that image so strongly because of those similarities. The point of my collage and the pictures is to give myself a visual anchor, because I know that I need one — and choosing an image that doesn’t fit is going to do more damage than unintentionally incorporating a little bit of Mal Reynolds into Ethan McCabe, because I’ll be engaging with a different text (even if it’s just the text of celebrity gossip) and fighting the associations that it brings.

Now it’s time for yet another sub-tangent, so that anyone still reading this has background on my relationship with Firefly and Serenity, and my confusion over whether including a few references were ethical, and the process I used in making those decisions are, again, clearer.

I’m a huge fan of Joss Whedon’s work. I watched Buffy and Angel religiously, have read fanfic and comic books, and — if my schedule had allowed — I probably would have watched Firefly when it first appeared on TV.

But I didn’t. And I didn’t watch the Firefly series until my friend Artemis sent me the DVD set as a birthday present in September of 2004. I watched them once, thought the series was beyond awesome, and then my little sister borrowed the DVDs and I didn’t see them again until after I’d finished writing DEMON NIGHT.

I didn’t get a chance to see Serenity in the theater, because I was on deadline and movies were out. But my sister bought a copy, and I borrowed it and watched it on DVD once. Again, I thought it was beyond awesome. Again, I was busy writing, so that was pretty much it. I thought about the movie, the series, and the characters, but my discussion of them and engagement with the texts were pretty limited (compared to some of my other interests.)

So this was all a very long way to say that I was aware of the superficial similarities between my text and the Firefly/Serenity texts, and Ethan and Mal Reynolds. And honestly — I’m okay with superficial similarities. They are very probably inescapable in genre fiction, whatever the medium.

And to bring it back to the main point, this is why the question of “how does an author know†leaves me a little confused. Because it’s all about awareness — and how can a writer not be aware of their text? Every word is a choice, isn’t it? Some choices are easier than others, but if a writer isn’t choosing, isn’t thinking about that choice and questioning their decision … well, shit — I don’t know what they’re doing. This is something I simply don’t understand. I can understand (though it’s very, very hard for me to imagine someone NOT knowing) that someone might not know it’s wrong and unethical to plagiarize (and if you don’t know, please visit Dear Author and Smart Bitches and read some of the latest discussions there) — but I don’t get how they can add something that’s not theirs without realizing it, without being aware.

But I also think that wasn’t the question Micki is asking. Because if she’s worrying about unintentionally lifting something, then she’s aware.

(And because this is a good time to say it again: Plagiarism is taking what’s not yours and saying that it is.)

So here, finally, is where I get to a real example. A little more background: I must have been in my teens the first time I heard the term “lip weasel†used to describe a handlebar mustache, and I’ve always loved the imagery, thought it was perfect. So when Ethan describes another character’s mustache, this is how he does it:

[…] Manny climbed out of his car. The silver medallions banding his black hat winked as brightly as his wheels. The brim cast a shadow down to his hooked nose and over a mustache that hung like a skinny dead ferret down the sides of his mouth.

In my rough draft, I used “like a skinny dead ferret†on the first pass, then changed it to “weasel†on the next, because “ferret†was making me uneasy. Then, after some thought, I changed it back to ferret, because A) “weasel†is (in my mind) a word loaded with more negative connotations than ferret, and people are often called weasels, but rarely are they called ferrets. My goal with this description was primarily to get the image across, not to make a suggestion about Manny’s character. B) I liked the sound of “ferret†better than “weasel†within the sentence, and it fit Ethan’s voice.

But I resisted changing it back to ferret even though the text was calling for it, and my instincts were telling me that I was making a mistake using weasel. I waffled until I wrote a conversation later in the book, when I bring the mustache up again. This takes place between Savi (whose vampire lover, Colin, has a distinct sense of right and wrong when it comes to fashion), Charlie (the heroine), who has never met Manny, and Ethan:

“Establishing a solid community in Seattle has become one of [Colin’s] new obsessions.†[Savi] caught her tongue briefly between her teeth, her eyes widening with amusement. “And I think it’s to spite Manny, too. The mustache offended him.â€

Charlie blinked and looked to Ethan, who said, “Her partner believes that no self-respecting vampire ought to have a varmint on his lip.â€

“Manny’s just a weasel all around,†Savi said […]

“Weasel†fit Savi’s voice; it didn’t fit Ethan’s. Plus, if I’d used it in the original description of that mustache, Savi’s last line would lose everything — it’d be redundant. So I gave in, and went back to the original description of the mustache and put in “ferret†where it should have been all along.

So, at this point, anyone who isn’t a fan of Firefly is probably scratching their heads and saying: What’s the big effing deal about the ferret?

Well, here’s the thing: in an episode of Firefly called “The Message,” Mal Reynolds tells this story about a military officer who had a “lip ferret.†It’s funny as hell, it’s memorable (I can barely remember anything else about that episode, because I haven’t watched it again, but I remember the phrase “lip ferretâ€) and it’s a unique way to describe the mustache. And as I’m writing this book, I am doing everything I can to not blur Ethan and Mal in any way, or to take from the Firefly writers anything that isn’t mine.

Because although an actor brings a LOT to a character in a television medium, IMO characters are still largely defined by their word choices. And it makes me uneasy to use the same word to describe the same thing, even though — in almost any other circumstance — I wouldn’t have much of a problem exchanging weasel for ferret (if the image I was trying to create depended on the shape of the animal.)

So I fretted. I worried. My gut was telling me that “ferret†worked better, but at the same time, I was wondering, “do I think it works better because of Mal?†and “Did I think of using ‘ferret’ because of that scene in Firefly?â€

In the end, the thing that trumped every other concern was this: it fit the text, and it fit Ethan’s voice. “Ferret†would have been a word he used even if I’d never watched Firefly.

It also wasn’t a direct quote. Even though I was familiar with the term “lip weasel,†Ethan wouldn’t have used it. But if I’d put “lip ferret†into his mouth … in my opinion, I would have crossed a line, because that phrase is something (to my mind) belongs to Mal. But the image of a weasel/ferret as a mustache doesn’t — that is anyone’s to use.

Okay, so what about something where they DO use the same phrase? I have one of those — and, again, it was one I changed and changed and changed again.

In this case, I’d written a scene where Ethan is pissed off when Charlie seems to be depending on him too much, and thinking of him as a hero — and then later, he’s pissed at himself for thinking of her in terms that go beyond his role as a protector. This takes place right after he saves her from a couple of vampires (he’s flying and they’ve just put her coat on, which is why her legs are around his waist):

Her hair was blowing against his face, caught in the seam of his lips. Her thighs tightened at the sides of his hips, and she lifted her hand to his mouth, dragging the strands away with a curl of her finger. “Thank you, Ethan.â€

He gave an abrupt nod. “It’s what I do.â€

Now, this one I wrote and didn’t have any problems with, until — after I was done with the book — I watched Serenity again. Then I realized that Mal Reynolds says “It’s what I do, darlin’†to a psychic female character who asks him if he understands his role. (Ah, god — trying to explain it doesn’t work. Here are the lines from memory, so they might not be perfect:)

(They are about to go rob a bank.)

MAL: Do you understand your role in all of this?

RIVER, the psychic: Do you? (cryptically)

MAL: It’s what I do, darlin’. (repeats to himself a little less cockily) It’s what I do.

And I was like: Holy gut-churning shit. Did I steal that?

Once again, I began changing the line. “It’s my job†sounded terrible coming out of Ethan’s mouth. I took away his verbal response entirely, and just had him nod … but that didn’t work. Because Ethan, at this point, isn’t just trying to warn Charlie against seeing something more to their relationship, he’s trying to convince himself, and remind himself of his role — and man, her legs are wrapped around him. Just nodding could be interpreted only as brusque acceptance of her gratitude, and there’s more than that going on here. There’s acknowledgement, but there’s also dismissal. And his verbal response makes that very clear (and it needs to be clear) in a way that an abrupt nod can only suggest.

In any case, “It’s what I do†isn’t a Mal Reynolds phrase. It’s a common phrase. If you Google “lip ferret†you’re going to hit a billion Firefly sites — if you Google “It’s what I do†you’re going to hit a bunch of other sites before landing on the quote from Serenity.

And, again — it’s what Ethan would say, even if I’d never watched Firefly. This was one of those instances of synchronicity in texts that really isn’t all that uncommon (nothing like, say, two men independently inventing calculus or developing theories of evolution). You just happen to notice it because you’re paying attention. And if I hadn’t been so aware of the similarities between the two texts and making certain I wasn’t copying, this never would have tripped for me, and would never had made me uneasy. If, for example, I’d been re-watching any other movie (or even Buffy or Angel) and a character said, “It’s what I do†I probably wouldn’t have had any reaction other than, “hee hee, Ethan said that, too†— if I had a reaction at all.

Okay. I have a couple of more examples of places where I do take stuff (and don’t attribute it), but this is a good place to pause, and say again: Plagiarism is when you take something that isn’t yours, and say that it is.

Now, looking back at what I’ve written about the two examples above, one thing pops out at me — in both cases, these were things that wouldn’t fit the text and character any other way. That’s what I’m talking about when I say that I own these, that I’ve made them the characters’, and I’ve made them mine.

I know that it is very, very possible that the only reason Ethan wouldn’t say “weasel†instead of “ferret†is because — somewhere in my head — hearing Mal Reynolds say it in his television-cowboy speak informed my idea of Ethan’s faux-cowboy speak. (Ethan adopted a certain way of speaking that is a crucial part of his history and character — and he’s as aware of it as I am.) It may have; I honestly don’t know. It might have been all of the Louis L’Amour westerns I read as a kid, crushing on Bruce Campbell in The Adventures of Brisco County, Jr. when I was a teenager, or a hundred thousand other places I picked up faux-cowboy speak.

Whatever is swirling around in my head, whatever source(s) it has, it has created something that might be labeled “Meljean’s Idea of Faux Cowboy Speak.†I’ve made it mine.

Being informed by another text is different than stealing it — and sometimes you have to wrestle with a word or phrase you’ve chosen to make certain that it really is yours, question and pound on it and beat it up … but once you’ve settled that it is yours, you keep on going.

And even when it’s not yours — you still have to make it fit the text, and — if it all possible, clue in the reader.

Sometimes, there’s just no good place to clue in the reader. Sometimes there’s just not. And sometimes, you don’t need to clue in the reader, because they’re part of an audience that’s going to get it.

That doesn’t mean everyone will. Nope, sometimes it’ll zip right over their heads … and sometimes, that’s okay.

So, this is one example. This is getting a bit deeper, IMO, into shades of grey. And here’s the setup: Jake is a novice (which just means he hasn’t gone through his hundred years of training) and in my world, novice Guardians who have just returned to Earth are susceptible to Enthrallment (which is pretty much like getting drunk on sensory input.) Jake has been away from Earth for forty years, and he’s cramming in as much pop culture as he can (I’ve established this earlier in the book; later in the book, I show how the novices are cloistered together in a training facility, and in their free time gather around, watching movies and such.)

And in the middle of a fight scene, a house catches on fire. Jake and Ethan are separated at the beginning of the scene, and when Jake catches up to Ethan, he’s suffering from Enthrallment. This is what he says after the fight is over:

“I heard you flying over the lake, but it sounded like you were having a private conversation, so I stayed behind. Then when I got there the house was burning, and it was just, ‘Fire, pretty’ and I lost it. I saw you take off fighting, but I didn’t think I’d catch up to you.â€

Fans of Buffy are probably going to get it. Readers who aren’t Buffy fans might wonder if the quotation marks around “Fire, pretty†are there because they set off a quote from an outside source, but the quotation marks themselves aren’t necessarily an indicator that it is … it could be just Jake recounting his earlier reaction.

But here’s why I’m okay with putting that in there without attributing it: I never intend for anyone to take “Fire, pretty†as mine, and I assume that a good portion of my audience is going to recognize it. Not as many as would recognize a line from Shakespeare, certainly — but it isn’t really obscure, and it is a reasonable thing for a character like Jake to say.

Because, honestly — I can’t imagine that novice Guardians (and their vampire friends) who have access to DVDs wouldn’t be getting together to check out stuff like Buffy. I can’t imagine that they wouldn’t pick up some of the catchphrases and toss them around to one another, and that these phrases wouldn’t enter into their everyday speech.

Do I say it in the book? No, because it wouldn’t be like Ethan to know or care where the phrase came from, and I can’t imagine Jake saying in the next sentence: “You know, ‘Fire, pretty,’ just like in Buffy? You know, ‘Beer, bad…’ Oh forget it.†In another scene, maybe I would have made the attribution clear in that way, just to avoid confusion; in this scene, however, the mood is too somber to pull something like that.

And for those readers who do recognize it, I also assume that they will take it as a ping! and they might have insight into the details of a novices’ activities that a reader who isn’t a fan of Buffy won’t get. Does it hurt a non-fan reader (or a fan who doesn’t pick up on it)? Not really. If knowing that the novices watch Buffy was important to the story, I’d make it explicit.

So it is a wink, but isn’t a furtive or a sly wink, and it is a wink that fits. It works for his character, and it works in context (the Enthrallment comparable to being drunk). It isn’t mine, but it is something I have woven in as cleanly as I can in every possible way, while also doing everything I can to let readers know through Jake’s character and lifestyle that I’m not saying it’s mine.

Later in the book, I have another one, where my heroine calls someone a “big damn hero.†That one isn’t even set off in quotation marks, and it’s quite a bit more obscure than the Buffy quote (it’s from a Firefly episode … I can’t remember the name of the episode, but “big damn hero†has grown beyond that episode anyway, if not beyond the fandom). But it is a phrase that fits the speech Charlie’s making at the time (it’s all a huge spoiler, so I can’t even give context), I’ve established that she likes action/adventure and sci-fi, and she works in a bar across from a movie theater in Seattle where twenty- and thirty-somethings sit around and bullshit with each other over all kinds of stuff. I have no reason to believe she wouldn’t pick up a phrase like “big damn hero†and use it.

Still, I wondered with both of these — should I use them? In both cases, I decided to, because they fit. And I wanted to make a direct nod to Firefly/Serenity. Which sounds funny after everything I did to keep from taking from it, but in the course of writing the book, I realized that unlike DEMON ANGEL and DEMON MOON, which I knew were rooted in and primarily inspired by literary sources, DEMON NIGHT was my movie book. It feels more like an action movie to me, a cross-genre movie, which is what Joss Whedon has really mastered, throwing in action, romance, comedy, drama, the works. And the speech that Charlie’s making is drawing on the concept of heroes in movies very explicitly; putting “big damn hero†in there worked on the surface and at a deeper level.

It also helped that Ethan wasn’t the one saying it, and Mal Reynolds wasn’t the one who’d originally said it — I didn’t have to deal with that tension, only negotiate between audience recognition and context.

Also, when I took out the “damn,†it sounded really stupid.

I wonder now if part of my decision to leave them in was because these are spoken examples — I don’t think I’d have used either one if it was part of the narrative, unless I was deep in the character POV and essentially recording their thoughts.

Okay, another pause here on a sub-tangent, because audience, character, and reader recognition probably needs to be addressed. And, again, this is something else that you often have to go with your gut, because there is really no good way to guess how many people are going to pick up on your references.

If I have a character who I’ve established as familiar with the online writing/reading community, and in her speech she uses the phrase “clue cake†… that’s okay. It won’t mean anything to someone who has never read Miss Snark’s blog, Jenny Crusie’s blog, or the Smart Bitches — but for those who do, it will be obvious where it came from.

What shouldn’t be in that book? An exchange like this:

Character One: Get yourself a piece of clue cake, okay?

Character Two: “Clue cake?†Is that supposed to be snarky? You’re trying way too hard, girl.

I mean, OH MY FUCKING GOD. There is nothing there that’s really “lifted†in the sense of being word-for-word stolen. And it is okay to use “clue cake†— it really is. There are words and phrases that pass into speech for certain specialized audiences (in this case, a romance-bloglandia audience) and if your character is a part of that audience, it’s okay if they use the term (even if they didn’t coin it. You don’t need to call up Miss Snark and ask permission to use “clue cake†because, IMO, it’s gone beyond her original use. Some people might disagree, it’s too obscure, but that is where you have to make an ethical decision, based on your knowledge of the phrase and its use.)

But to lift that exchange and pretend it’s yours? NO NO NO NO! The only way I can even conceive of that being okay is if you e-mailed Jenny Crusie, and said: Hey, I want to put this in my book. Can I?

And if she says yes, I hope to god you put an acknowledgement on the front page. And I hope to god that your first character is someone like Miss Snark, and your second is someone like Crusie — because otherwise, why would your characters ever, ever, EVER have that exchange? The only reason would be because a writer liked it, and they wanted to use it … but IMO you just don’t go sticking stuff willy-nilly into your manuscript because you like it. It has to be organic, it has to be owned by the text, the characters, and you.

You can’t take something and use it in your own way just because you like it and you might use it in real life. A writer has to separate herself from the book. You have to. You have to. Every writer has his or her own voice, but just because I would use “clue cake†in a conversation with another romance-blogging friend, it doesn’t mean I should stick it into my text … unless the text and characters call for it.

This is why I keep harping on context, and sticking in examples and explaining the setup. Your characters’ experiences and background DO matter. Their voices matter. You should know them inside and out, and question all the time whether they’d use a phrase from an outside source. It is not a question of whether YOU would use the phrase; it’s whether THEY would.

That’s also why I feel there is a tiny bit more leeway in a character’s speech than there is in the narrative text — but still, you have to be aware of what you’re using, why you’re using it, and how you’re using it. And if you aren’t using it for the right reasons (ie, you’re just using it because you liked it, you thought it was funny, you thought it was pretty) get rid of it and give your characters something of their own, something they really would say.

And also, I keep saying “word†or “phrase.†That’s because, IMO, any more and you venture into DO NOT DO THAT territory. People don’t incorporate whole sentences into their speech. (I’m not really talking about quoting a line from The Princess Bride or something — we all throw that out — because there is an awareness that you ARE quoting; there is never any sense that it is yours.)

If your character is saying something beyond a small phrase that they might have picked up and incorporated into their own speech patterns — you have to put quote marks around it, at least.

And if it is in the narrative … okay, I can’t think of any good reason for a longer phrase, sentence, or paragraph to be used in the narrative (unless it is a passage being read from a book, but that format automatically includes some type of attribution — and even if the book isn’t identified in the text (cough author’s note cough) it’s obvious to a reader that it is a quoted passage, so it’s not the same).

Here’s the thing: every thing in the book should either be in your narrative voice or the characters’ voices. And when you bring in something from outside, it’s not in your voice. So you have to play with it and work it and mold it until it is. Sometimes that means picking up a word and using it (that’s okay — if a description you read of the Notre Dame mentions buttresses, and you use “buttresses†in your text, it’s not a problem. Because, they’re buttresses, and there’s really only one good word to use, no matter the voice.) But your description should not just be a paraphrasing of the description you read. (Better yet: read a couple of descriptions. Look at pictures. Really, really get an idea of what it looks like, so that you can describe it in your own words.) Because when it comes out, we should see it through your character’s eyes, hear it through your character’s voice. You can’t just call it your own; you have to make it your own.

Again, you’ll know if it’s not your own. If you’ve got a book open and a thesaurus, you’ve got issues. But if you’re scraping and changing and working a piece of outside information into your text, you’re probably okay. Adding a chunk (and by “chunk†I mean, “more than a word or a small phraseâ€) of outside information isn’t something that you can do blindly — and if you do somehow incorporate the same phrase from a description that you read a year ago on the ‘net or in a book, you don’t have to beat yourself up over it.

The key is always being aware. And I just don’t know how any writer can NOT be aware of their text, and what they’re putting into it, and how they’re using it. So, Micki — you’re questioning, and that’s the most important part when it comes to avoiding plagiarism, and making ethical decisions about what to include.

So, a few things to try to sum up.

Plagiarism is taking something that’s not yours, and saying it is.

If you know (awareness is key!) that your words are coming from somewhere else, and it’s easy to write, you’re probably doing something wrong. Question every word you put in. Do I need this? Would my character say this? Does this say something about my character? Does the plot need this?

Aside: if you’ve never heard the term “lip ferret†before, and you happen to use it in your text, it’s not a big deal, and it’s not plagiarizing. You might get an e-mail from someone saying, “Did you take that from Firefly?†and you might pull your hair out and feel stupid for about five minutes … but really, these kind of things happen, and you just move on. In my case, it was different, because I *was* aware of the term, and using it under those particular circumstances would have been an ethical breach, IMO.

Liking something isn’t enough of a reason to use it. Here’s my advice if you run across something that you love and you really, really want to use: tear it the fuck apart. Strip it naked, skin it, fillet it, then dismember it. Watch how it bleeds. Look at all the parts. Step back, take another look at it as part of the larger picture of plot and character and theme. Learn how it works — and then, instead of using that line, or that joke, or that scene, you’ve learned how to construct your own with your character’s voice, your narrator’s voice, whatever. Then you put that in your toolbox to pull out later.

Writing isn’t always about creating; sometimes you have to be destructive. Sometimes you have to take something wonderful — a description, a scene, a plot — and rip it up into ugly little pieces so that you can make it your own. Since I’m going into gruesome territory, it’s a lot like chewing up a bunch of different things, and vomiting it back out. And if you see something swimming in the vomit that isn’t yours, if you wonder “what the hell is that doing undigested†or worse, “when the hell did I eat THAT?†you have got to go in there and either take it out — or chew it up some more.

And maybe it won’t be as pretty when it comes out — but it will be yours. And that’s what counts.

What plagiarism really comes down to is laziness. A writer who is rigorous and aware of what they’re putting into their text probably isn’t going to be plagiarizing.

Laziness is a writer who doesn’t want to think of their own plot, so they take another. (Note: This doesn’t apply to retellings of out-of-copyright works (such as Clueless and Emma, Bridget Jones’s Diary and Pride and Prejudice.) I love twice-told fairy tales — but if you are basing your story on Robin McKinley’s retelling of Deerskin instead of using the original fairy tale as a plot frame for your own retelling, IMO that’s lazy writing. And it’s unethical.)

And it’s okay if you have a scene that mirrors another scene in a book — synchronicity does happen. But it’s unethical to deliberately mirror that scene because you want it for your own, and because it does what you want your story to do.

This isn’t about being caught. This is about intent, and about making ethical decisions when you’re writing. Every (most) romance novel out there has a scene where the hero and heroine declare their love, and they move into the realm of happily-ever-after. It is inevitable that some of these scenes will be similar.

But there is a difference between writing a scene that flows organically from your plot and characters and being aware (usually with a really crappy feeling in your gut) that there are some similarities between it and another scene you might have read. Very likely, you’re going to fight it … but sometimes, scenes just won’t be written any other way, and you have to let it go. The important thing is, you own that scene. It’s yours. It might not be perfectly original, but it’s yours and it fits your book.

But if you are writing a happily-ever-after scene, and you think, “I really love the way Dirk Steele** told Mary that he loved her in Book X and wasn’t that so emotional?†so you write your scene in the same way, hoping that you create the same emotional reaction that you got from the other book, that’s unethical. It just is. It’s stealing, you don’t own it, you didn’t make it yours and your characters’ — you just took something from someone else and pretended it was your own.

That is why you have to tear what you love apart. Ask “how does that work?†and “how does it relate to the characters†and then, if you learn from it and add it to your vomit toolbox of “how to create an amazing emotional reaction†and you take bits and pieces of the bones and flesh that made up that scene (along with a thousand other bits and pieces that are floating around in the vomit toolbox) in a way that is organic to your own characters and the text, you’ve made it your own, and you’re okay.

And you’ll know it in your gut.

**RE: Dirk Steele. This is one of those things that you write and you don’t quite know why — I was trying to think of a stereotypical hero name, and Dirk popped into my head as a first name, and Steele came really easily after that. Too easily, because I know that names NEVER come that easy to me. So I was like, why is that?

Then I was like, Duh! Marjorie Liu has a series called Dirk & Steele. Here’s ethics in action — in a manuscript, I’d take it out because it is too much of me in it, even though it is a nice nod to Marjorie’s fantastic series. But here, I’ll leave it in, because this is me writing, and she’s got a new book in the series coming out next week called THE LAST TWILIGHT, and I’m more than happy to give her a nod here. Because Marjorie — well, if you’re ever looking for a writer who can’t be called lazy in any way, that’s her.